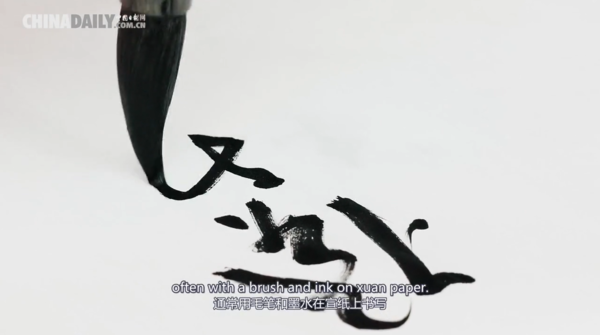

A Brush with History

|

| Click the photo and watch the video. |

Chinese calligraphy is the artistic vehicle in which the nation's cultural lineage is carried.

Editor's note: There are 43 items inscribed on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage lists that not only bear witness to the past glories of Chinese civilization, but also continue to shine today. China Daily looks at the protection and inheritance of some of these cultural legacies. In this installment, we trace the aesthetic and cultural lines that connect the first Chinese scholars with the brush-wielding enthusiasts and practitioners today.

When Zhuo Heng entered a showroom of the National Art Museum of China one day in late November, she was startled by the bustling scene of visitors viewing the calligraphy scrolls. The exhibition was dedicated to the work of Chen Hailiang, a calligrapher of repute who has gained recognition particularly for writing caoshu, the cursive script that presents the most freedom and boldness in Chinese writing.

An amateur calligraphy practitioner herself, Zhuo says Chen's works caught her deeply at first sight.

"I was awed, not only by his mastery of the art — he is well-versed in all the scripts and in making works of different sizes, varying from those measuring dozens of centimeters to several meters from the floor to ceiling, and he has shown the grandeur of calligraphy," she says.

"But also, how he breaks certain rules to form a distinctive style of his own surprised me a great deal."

Zhuo refers to the many areas in Chen's writing pieces where too much ink is accumulated, and look like big stains. She says it is normally seen as wrong and should be avoided.

To her even greater surprise, Chen was in the showroom that day, providing a guided tour and a calligraphy demonstration to the audience. Zhuo joined the group and put forward her question about the accumulations.

"He told me, it (not following the rules) is totally fine; he said, when raising up the brush, try to forget these rules and regulations of how you should orchestrate the strokes correctly, and just focus on how to awaken your mind and give the full expression of your feelings on the paper," Zhuo recalls.

"I felt relief hearing his words. I had often felt tense when practicing, fearing I would make mistakes — it is funny because I practice trying to calm myself — but now I know how to write, truly, with ease."

Zhuo was not the only one enchanted by calligraphy that day.

As well as Chen's one-man exhibition, a separate exhibition, Purity and Glory, which marked the 70th anniversary of the Buddhist Association of China, was also creating quite a stir.

The exhibition displayed fine and rarely seen calligraphic works of important figures, such as Zhao Puchu, the former chairman of the Buddhist Association of China, and Hongyi, the master monk whose last piece of writing, done three days before his passing, was on display and drawing crowds of onlookers.

Days later, another calligraphy show, featuring the work of the great painter Liu Haisu, was opened at the National Art Museum of China to continue inspiring people's enthusiasm for the long-standing art of writing.

With an artistic legacy of thousands of years, Chinese calligraphy seems unlikely to lose its status in the heart of people, even in a time when handwriting has decreased sharply. It was, at one time, viewed by people as a high form of artistic worship at museums, while at other times, simply a practice so common that lovers of the art, both professionals and amateurs, would write on a daily basis.

Expressive Strokes

The birth and early evolution of Chinese calligraphy began with the formation of Chinese characters millennia ago, including those of such pictorial simplicity that were engraved on animal bones and tortoise shells, and the ones cast on bronze vessels that became neat and elaborate.

A significant development of the calligraphic script is the widely known shiguwen, or the inscriptions on stone drums, believed to date back 2,000 years. It is deemed the "ancestral form", upon which Qinshihuang, the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), unified the writing of characters, one of the important measures taken to unify the land and people he ruled over.

The unique script of shiguwen made it a topic of discussion after several stone drums were discovered during the early Tang Dynasty (618-907). The style inspired interest among artists for its structural grace and the majestic mood being presented.

Shiguwen ushered in the invention of dazhuan (the large-seal script), and xiaozhuan (the small-seal script) that was simpler in structure. These were followed by lishu (the clerical script), kaishu (the regular script), xingshu (the running script) and caoshu (the cursive script).

These scripts have been executed predominantly by learned people.

Practicing calligraphy becomes a carefree dance of the Chinese brush on paper, that is far beyond communicating the meanings of the characters being written. It is a silent symphony orchestrated by the fluidity of ink and water, and a ritual enforced by the energies of hands for one to cultivate himself, and to connect with the universe.

Such writing unites Chinese people living in different corners of the country from all walks of life, reinforcing that intention by adding dimensions of artistry and spirituality. Be it a scholar, a painter, a calligrapher or someone amateur, they share the pleasure brought by calligraphy.

In 2009, Chinese calligraphy was added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

The essential role calligraphy plays in Chinese cultural tradition is also evident in the close association between it and painting. Normally, they are mentioned in a union as shuhua (calligraphy and painting).

A Chinese painting often bears calligraphy, added by its creator or collectors and viewers, to accentuate a literary temperament. It can be an autograph, a poem, a commentary, a note to the one who is to receive the painting as a gift, or simply a seal impression of the artist's name or pseudonym — a smaller form of calligraphy that demands the delicate techniques of hand engraving.

Zhao Mengfu, a great artist who lived during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), asserted the equivalence of the two forms not only in presenting brushwork brilliance, but also as the vehicles of self-expression.

"Calligraphy and painting are basically of the same creative source," he said.

The continuous reforms in execution by exponent figures like Zhao helped regenerate calligraphy throughout centuries, through their efforts to be a consummate artist.

Meanwhile, there have been personalities who articulate the importance of appreciating calligraphy in the course of public education. Perhaps outperforming them all is Liang Qichao, the foremost intellectual and educator of modern China, who considered the research and promotion of calligraphy an integral part of his life's work.

Liang's contribution to the calligraphy renaissance of his time is hailed at Old China's New Citizen, an ongoing exhibition to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth at the Tsinghua University Art Museum, which runs until Jan 14. His collection of calligraphy rubbings and his own written works are on show.

Du Pengfei, executive director of the museum, says Liang was a great man who "believed in the necessity of cultivating an interest in things of aesthetic value, such as calligraphy".

He says Liang was devoted to the study of calligraphy and to spreading its beauty, and the significance of carrying on Chinese cultural lineage, to the public.

In 1926, Liang gave a speech titled "A Guide to Calligraphy" at the Tsinghua campus, during which he said that "calligraphy is the most beautiful and convenient tool for entertaining … to sooth one's heart and mind". He went on to note that "calligraphy shows the beauty of lines, the reflective glare of ink, and the strength of handwriting".

He donated a large part of his collection of ancient tablet rubbings to the Beiping Library, now the National Library of China.

Modern Twist

The evolution of calligraphy continues even now.

For example, the timeless beauty of shiguwen continued through to the 20th century among artists and scholars who kept copying the script.

Wu Changshuo, a leading reformer of the ink tradition, is famed for integrating the calligraphic brushwork of shiguwen into painting.

Today, some endeavors are done in an avant-garde gesture and shown at art galleries like INKstudio which has spaces in Beijing and New York.

The decade-old gallery introduces to both domestic and global audiences experimental approaches to add new perspectives to ink art and calligraphy, as a rich, complex art language and also as the distinctive worldview of China and East Asia, according to Craig Yee, who co-founded INKstudio alongside two Stanford University alumni.

Artists who have been shown at the gallery include the likes of Wang Dongling and Wei Ligang. Their works have aroused discussions and debates, which from Yee's point of view, are "very important to expand the possibilities" and degrees of freedom in the realm of calligraphy and ink art, the same way as their predecessors did.

Just as Liang Qichao once put it: "There is no better way (for one) to best express the personality of a person than calligraphy."

(Source: China Daily)

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号