Rabbit God: 'Image Ambassador' for Beijing

Every year, during the Mid-Autumn Festival (on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month), Chinese families customarily have reunion dinners. After the meals, the families worship and watch the moon. In addition to mooncakes and fruits, Beijingers use clay figurines of the Rabbit God as sacrificial offerings to the moon, to pray for peace and good luck.

The Rabbit God is in the shape of a rabbit man. In Chinese mythology, there was a rabbit that lived on the moon. Every day it made herbal medicine for the Queen Mother of the West. One year, a serious epidemic broke out in Beijing and many people were on the verge of death. In face of the crisis, the rabbit transformed itself into a man, and descended to the Earth to treat the people. Out of appreciation for what the rabbit had done, craftspeople made clay figures with rabbits' heads and humans' bodies, so Beijingers could use them as sacrificial offerings to the moon during the Mid-Autumn Festival. The custom dates back hundreds of years ago. In 2009, the craft of making figurines of the Rabbit God was added to the list of Beijing's municipal intangible cultural heritage.

Folk Customs

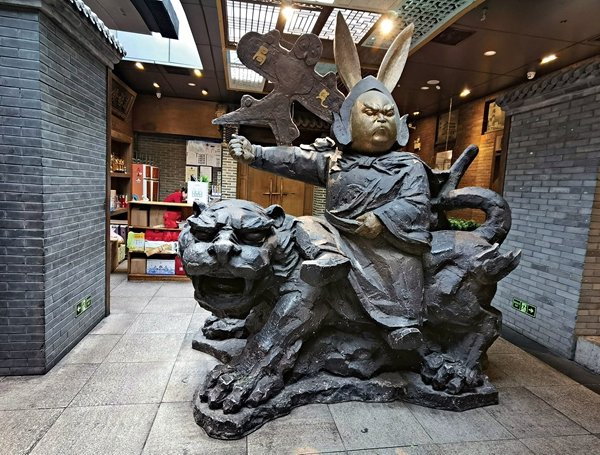

The origins of the Rabbit God can be traced back to the ancient custom of moon worship. In Chinese mythology, Chang'e, or the Goddess of the Moon, lived in a moon palace with a jade rabbit and an osmanthus tree. Therefore, in the Chinese culture, Chang'e, the jade rabbit and the osmanthus tree can all be used as metaphors for the moon. Later, beginning from the Ming (1368-1644) or Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), the symbol of the jade rabbit gradually developed its own significance. Artistically treated and personified, the Rabbit God eventually has a regular image, with the head of a rabbit and the body of a human, wearing armor, banners (on its back), and holding a mallet for grinding herbal medicine. The rabbit usually rides an auspicious animal.

During the period from the Ming and Qing dynasties to the Republic of China (1912-1949), many workshops in Beijing made and sold figurines of the Rabbit God in various shapes. Around the Mid-Autumn Festival, the figurines were displayed in booths along both sides of streets in Beijing's business districts.

Out of respect for the Rabbit God, many Chinese referred to the act of buying the god's figurine as "inviting the Rabbit God home." On the Mid-Autumn Day, a Chinese family usually had dinner together and then waited for the moon to appear. When the moon rose, the hostess (of the family) conducted the moon worship ceremony. A table was set up in the southeast corner of the courtyard, on which candles, mooncakes and fruits were arranged. Most important of all, the honorable figurine of the Rabbit God was placed. After the ceremony was completed, the family ate the fruits and cakes, and the figurine became a toy for the children.

As figurines of the Rabbit God were made from clay, they were fragile and easily broken. And even if they were well-preserved, the figurines would be intentionally smashed on the eve of the Chinese New Year every year. Why? The act symbolized a family would get rid of all the bad luck and ailments that the family's members suffered during the previous year, and that they prayed for peace and good health during the coming year. Before the following Mid-Autumn Festival, Chinese would once again "invite" new figurines of the Rabbit God into their homes. Since the figurines symbolized good wishes of the people, Chinese customarily gave the items, as tokens of happiness, to their friends or relatives during weddings, celebrations to open businesses, or other festive occasions.

New Image

For a period before the 1980s, dissemination of traditional Chinese culture, including folk customs and traditional crafts, came to a standstill. It was not until after China implemented its policy of reform and opening up in 1978 that the customs and crafts were gradually revived. Given the revival of the traditional Chinese crafts, many experienced artisans resumed creating crafts.

After the craft of making figurines of the Rabbit God was revived, the items appeared in Beijing's markets. Numerous Chinese, who visited temple fairs, favored the lovely figurines. Hu Pengfei, a craftsman from Fengxiang (a county in Baoji, a city in Northwest China's Shaanxi Province), saw the business opportunity in the craft.

Hu was born into a family of craftspeople in Fengxiang, which is commonly referred to as the "hometown of the traditional Chinese clay figurines." He began learning, from his parents and grandfather, how to make clay figurines at an early age.

In 2001, then-19-year-old Hu went to Beijing to develop his career. He soon noticed many Beijingers liked figurines of the Rabbit God. As he was aware there was a lack of artisans who could make the figurines, Hu learned the craft from skilled craftspeople. He also collected materials about and pictures of the Rabbit God.

During the Mid-Autumn Festival of 2008, hundreds of Hu's Rabbit God figurines were displayed during the temple fair at the Dongyue Temple (in Beijing). The figurines, which were arranged on a several-meter-high shelf, were called the "Rabbit God Mountain" by Beijingers. Within a few days, all the cute rabbit figurines were "invited" home by the visitors to the temple. At the end of that year, the "Rabbit God Mountain" also sold well during the Book Fair at the Temple of Earth and the temple fair during the Spring Festival.

During the past decade, Hu's art studio, established by him and several partners, has evolved into a craft plant with several hundred workers, including a core team, whose members are dedicated to the design, marketing and R&D (research and development) of crafts. Hu has also registered a brand name — Jitufang (which literally means "lucky rabbit studio") — for the rabbit figurines created and sold by his plant, so it would be easier to expand his business.

While traveling through Beijing, many tourists purchase figurines of the Rabbit God as souvenirs. The figurines, with Beijing's distinctive features, embody people's desire to enjoy the good life. In recent years, some young people have begun studying the historical development and cultural significance of the Rabbit God. Some others have found new ways to interpret the god's cultural significance. As the figurines have become increasingly popular among Chinese, the Rabbit God has become the "Image Ambassador" for Beijing.

Inheritance, Innovation

To keep the intangible cultural heritage alive, Hu has led craftspeople with his plant in innovating the designs and the technical skills used to create figurines. Hu's team is composed of young craftspeople, whose average age is under 35. As they understand young people's preferences, the craftspeople can create figurines that meet young people's aesthetic tastes.

Hu's business operation model is different from that of the elder generation of artisans. According to Hu, "Folk crafts are commodities. Therefore, only when they have market value will the items be filled with 'vigorous vitality'." Based on the business ideology, Hu registered the brand name of Jitufang for his plant's figurines of the Rabbit God, and applied for patent protection for the images of his plant's Rabbit God figurines.

During the past several years, Hu has provided courses to primary and middle school students, to teach them how to make figurines of the Rabbit God. Hu has also arranged for the children to participate in cultural activities held by his art studio. He hopes children will learn more about the craft of creating the Rabbit God, so they can better understand the aesthetics and folk beliefs embodied by the traditional craft.

Photos Supplied by Jiao Feng and VCG

Source: China Today

(Women of China English Monthly)

Editor: Wang Shasha

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号