Millennia-Old Technique Reignites Passion for Porcelain

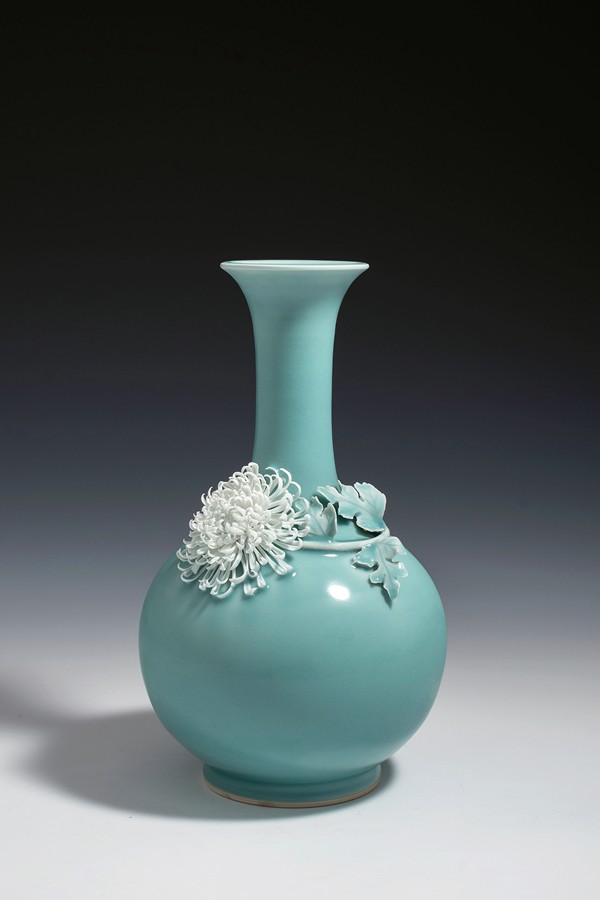

Longquan, a historical and cultural city in east China's Zhejiang Province, is known throughout the world for the production of celadon porcelains. Longquan celadon, with a history of more than 1,700 years, is a type of green-glazed porcelain. It is renowned for its jade-like glaze, and for its exquisite shape. In 2009, the traditional firing technology used to produce Longquan celadon was added to the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Diverse porcelains — ranging from those with complicated techniques, delicate and versatile forms, and time-honored history — have been produced throughout China's history. What makes Longquan celadon stand out? Why has it been dubbed "the jade of Chinese porcelains?"

Cultural Symbol

Longquan celadon dates back to the Three Kingdoms period (220-280). At that time, residents of Longquan began using the region's abundant mineral and kaolin resources to burn porcelains. Most of the kilns were located at the feet of the mountains, where streams or rivers flowed. The kilns were named "Long kilns," and the type of porcelains produced in the kilns was celadon. With improvements in the porcelain-making techniques, Longquan celadon became the preferred porcelain of the royal family during the Five Dynasties period (907-960).

Longquan celadon reached its golden era during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Local kilnsmen were able to fire celadon products that were "green like a jade, bright like a mirror, and sound like a bell (when tapped by a finger)." Influenced by the artistic aestheticism of the Song emperors, most of the Longquan celadon products had a primitive simplicity, and they were rarely decorated. During the late Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), the locals learned about porcelain-making techniques, from northern China, and they used those techniques to fire top-level, light-greenish-blue and plum-green glazes. Thus, Longquan celadon became a cultural symbol of the Song Dynasty. The celadon products, with their high-level glazed colors, were praised as "beautiful as jade." Longquan celadon has since been favored by porcelain lovers around the world.

However, the kilns in Longquan began to wane during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), due to a combination of declining export markets and the introduction of new kinds of porcelains. Almost all of the kilns were closed by the early 20th century.

More than 60 years ago, local experts and craftsmen were tasked with studying the firing technology used to make Longquan celadon, to reignite the kilns for celadon production, and to rejuvenate the city's celadon industry. Since then, many designers, experts and artists have been attracted to Longquan, where they have contributed to the inheritance and innovation of the celadon.

New Vitality

In recent years, the local government has made great efforts to promote the celadon-making technique, and to develop celadon kilns. Those efforts have helped to rejuvenate the city's celadon industry, and, in turn, they have contributed to the local economy. Many craftswomen have since become committed to protecting, inheriting and innovatively developing the celadon-making technique.

|

| Mao Danyang |

Mao Danyang, born in 1966, is the daughter of Mao Songlin, a master of celadon art. Influenced by her father, Mao Danyang has adhered to the concept of "making the past serve the present," and she has focused on making celadon pots. She makes various sizes of celadon pots. An exquisite small pot is only a few centimeters tall, while the height of a large pot is up to 50 centimeters. Mao Danyang's works have been collected by domestic and international museums and ceramic lovers.

|

| Yan Shaoying |

Yan Shaoying was born into a family of porcelain craftspeople in 1978. Yan studied the celadon-making technique under Chen Aiming, a master of ceramic art. Yan has innovatively integrated character-carving and claycarving techniques into the making of celadon products. Through her innovated technique, Yan has been able to ensure the color of the glaze is strong, and the outline of the celadon is finer and smoother. During recent years, she has made celadon flowerpots, celadon incense burners, and other celadon products, to share the charm of Longquan celadon with as many people as possible.

|

| Ye Fang |

Ye Fang, another Longquan celadon craftswoman, is also from a family of porcelain craftspeople. Influenced by her family, Ye learned how to make celadon products when she was young. In recent years, she has developed celadon products — with aesthetic, fashionable elements — in an innovative way.

Now, more than 30,000 people earn a living by making celadon products in Longquan, and their dedication to the industry enhances the possibility of protecting and developing the celadon-making technique. A diversity of celadon products has not only reappeared in the homes of many Chinese, but has also begun appearing in displays at exhibitions and in museums, both at home and abroad. That makes it a virtual certainty Longquan celadon, the jade-like porcelain, will continue to shine, not only in China, but also around the world.

Photos from Interviewees

(Women of China English Monthly November 2024)

Editor: Wang Shasha

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号