Weifang: A City of Crafts and Folk Arts

Weifang, in East China's Shandong Province, is known as the world's capital of kites, Chinese paintings and Chinese epigraphy. It has guqin, a traditional Chinese stringed musical instrument, and paper-cutting listed as masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In November 2021, Weifang was added to UNESCO's Creative Cities Network as a Crafts and Folk Arts City. Cities added to the network are "placing culture and creativity at the heart of their sustainable urban development," according to UNESCO.

Weifang is endowed with rich historical and cultural heritage. It is the birthplace of Dongyi culture, an important branch of Chinese civilization, where Qi culture, Lu culture, marine civilization and farming civilization blend together.

Weifang is well-known for its thriving crafts industry. Among the city's 17 national-level intangible cultural heritages, 10 are crafts and folk arts, such as kite-making techniques and woodblock New Year paintings, according to the city's government.

World's Capital of Kites

According to local historical records, Weifang kites were popular during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and they became a major folk art during the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), with many artists becoming widely known for their exquisite, high-flying creations.

In 1984, Weifang kites were sent to Shanghai to be displayed during an exhibition, and they impressed officials of an international kite association, who immediately suggested Weifang set up a global platform for the art. This led to the first Weifang International Kite Festival, held that same year. The city's kite sector has continued to grow, with the festival being held every year since 1984.

In 1988, Weifang was selected the world's capital of kites. The next year, World Kite Museum of Weifang was established.

There are currently more than 400 kite companies in the city, and they employ more than 80,000 people, combined. Each year, more than 220 million kites are made, with annual sales of more than 2 billion yuan (US $307 million), according to municipal authorities.

Yang Hongwei, 56, is a leading inheritor of Weifang's kite tradition. She was born into a kite-making family in Yangjiabu, a village in Weifang. At the age of 16, she learned kite-making skills from her grandfather, Yang Tongke. In 1992, after 10 years of practicing the craft, she set up her own workshop. Yang's creations include common butterfly and swallow patterns, as well as patterns and images from Chinese mythology, legends and history.

|

| Yang Hongwei |

"What people fly is not only a kite, but also their wishes and expectations for the future. The kites carry Weifang's profound history and culture, and connect history with modernity. I want to be the guardian of traditional kites and leave the cultural treasure to future generations," Yang Hongwei says.

She has been invited to visit Germany, Australia and other countries to share the stories of Yangjiabu kites, and to teach kite-making and -flying skills. To date, she has trained more than 10,000 people. She has been selected a Star of Qilu Culture and Master of Folk Crafts in Shandong Province.

Capital of Chinese Paintings

Yangjiabu is also known for its New Year paintings, which originated during the Ming Dynasty and thrived during the Qing Dynasty. Today, Yangjiabu is one of China's three major production bases of woodblock-printed New Year paintings, along with Yangliuqing, in North China's Tianjin, and Taohuawu, in Suzhou, in East China's Jiangsu Province.

|

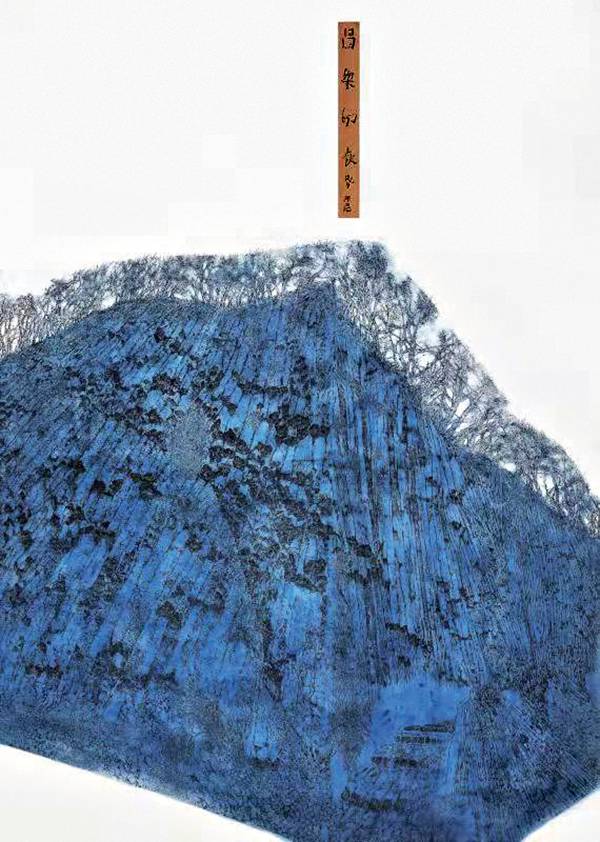

| Changle Impression |

Weifang is home to many accomplished artists, including Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145) and Guo Lancun (1902-1978). Zhang created the masterpiece, Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival, during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Zheng Banqiao (1693-1766), a famous painter and calligrapher during the Qing Dynasty, had been governor of Weifang for seven years. Those artists helped secure the important position of Weifang painting and calligraphy.

Qingzhou and Linqu, both in Weifang, have been named the hometowns of Chinese painting and calligraphy, respectively. In 2013, Weifang was named China's capital of painting during the opening ceremony of the third Chinese Painting Festival.

|

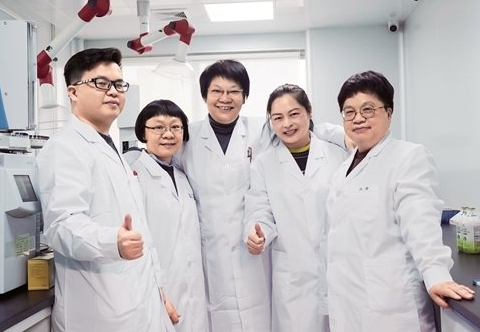

| Liu Lixia |

"The process of creating a painting is like having a dialogue with nature. It doesn't matter what you paint, or how you paint it. What matters is whether the work can express what you feel and understand," says Liu Lixia, a fine arts teacher of Lichang School, and a member of both the China Artists Association and China Hue Art Association.

Changle Impression is one of her representative paintings. "I created the painting after I visited the volcano ruins in Changle County, in Weifang, many times. Volcanoes give birth to sapphires and soil, which is the reason why I used blue as the basic color," Liu says. As a teacher, Liu has established a gourd pyrography class, to teach children the traditional craft.

Capital of Chinese Epigraphy

Weifang is the hometown of Chen Jieqi (1813-1884), a collector and epigraphy expert during the Qing Dynasty. Chen has been regarded as one of the most outstanding experts on epigraphy since the 19th century.

During his lifetime, he collected more than 7,000 ancient seals, and a large number of ancient bronze wares, including the precious Maogong tripod, a piece dating back to the late Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 BC) and bearing the longest text among all engraved bronze wares unearthed in China.

Based on his rich collection, Chen promoted epigraphy through the forms of rubbings, research and publications. His academic achievements greatly boosted the development of epigraphy, and they have been valued by the academic community. Given his achievements in epigraphy, Weifang has been referred to as the "holy land of epigraphy" and the "capital of Chinese epigraphy."

Many people in Weifang have learned calligraphy and seal cutting since childhood, and they have inherited and carried forward the culture of epigraphy.

Guo Nana is a member of Weifang Calligraphers' Association. Her works have been displayed during the Shandong women calligraphers' works exhibition. "I feel lucky to have been born in Weifang, a city with a rich cultural atmosphere," she says.

|

| Guo Nana |

Her grandfather, Guo Zixuan, is also a calligrapher. He has made more than 15,000 seals. Influenced by her grandfather, Guo Nana has also developed an interest in seal cutting. She thinks designing the print is the core and the most challenging part of making a seal.

Weifang's municipal Party (Communist Party of China) committee and government have always attached importance to the development of the cultural industry. They allocate special funding each year to reward people who have won awards in national cultural exhibitions and competitions. Weifang has also built many cultural industrial parks, to get the utmost of the city's rich historical and cultural legacies, and to boost cultural development and the creative industry.

Photos Supplied by Interviewees and VCG

(Women of China English Monthly July 2022 issue)

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号