Centenarian Doctor Committed to Defeating Leprosy

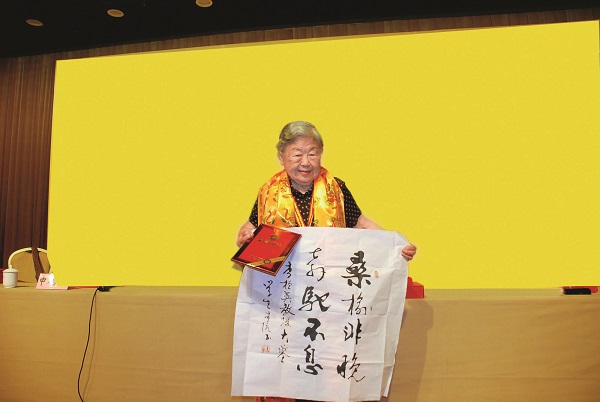

Li Huanying may be 101, but she is just as committed — and active, even though she doesn't travel as much — in efforts to prevent and treat leprosy. She for decades has been devoted to treating those once discriminated against by society, and she has consistently shared her leprosy research and therapies with the world. In March, the All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) named Li a National March 8th Red-Banner Pacesetter, one of the country's top honors for outstanding women, in recognition of her decades-long work.

Return to Motherland

Li was born into an intellectual family, in Beijing, on August 8, 1921. She made up her mind to become a doctor after she graduated from the School of Medicine, affiliated with Shanghai-based Tongji University, in 1945.

A year later, she went to the US to pursue a master's degree, in bacteriology and public health, at Johns Hopkins University (JHU), and worked as an assistant researcher at JHU after graduating from there. In 1950, Li, just 29 at the time, received an offer from the World Health Organization (WHO) to become one of its medical officers.

During the following seven years, Li travelled to many countries in Asia and America, where she helped people fight contagious diseases. Her efforts earned her great recognition from WHO, for her professionalism and devotion.

The WHO in 1957 offered to renew Li's contract for another five years. However, Li's patriotism prevailed after she heard the inspirational story of Qian Xuesen (1911-2009), a distinguished scientist and founder of China's aerospace industry, who had decided to return to China in October 1955.

"There was huge demand for talents to rebuild the country in the early years after the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) … As a Chinese, I was eager to return home, serve the people with my learning abroad, and sacrifice my best years to the motherland," Li recalls.

Therefore, she declined WHO's offer and, in 1958, she chose to leave the US for China without informing her parents of her decision.

By that time, her parents had emigrated to the US. During a meeting with them, in Hong Kong in 1964, which was then a British colony, Li's parents asked her to move to the US with them.

"As a doctor, if I were to leave China now, I would rather have never come back. It is my privilege to serve the country and the people," Li told them.

A Famous Doctor

In 1959, Li began working at the Institute of Dermatology, affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

In 1978, Li began working as a researcher, specializing in leprosy, with the newly established Beijing Tropical Medicine Research Institute, affiliated with Beijing Friendship Hospital.

Leprosy is a long-term infection caused by a strain of bacteria. Infection can lead to nerve damage, which generally results in disfigurement and disability. In the past, patients often suffered physical and mental torture because of people's ignorance about the contagious disease, and because of the shortage of medical resources.

In March 1979, Li arrived at Nanxing, a remote village, which had a large number of people afflicted with leprosy, in Mengla, a county in Southwest China's Yunnan Province. The village was called "Mafengzhai," which literally means "leprosy village" in Chinese.

Back then, many people, including doctors, refused to enter the village, and they kept a distance from the leprosy patients, as they feared contracting the disease.

Li met several young women afflicted with and tortured by leprosy upon her arrival. Their misery made her more determined to tackle the disease.

Serving as a visiting scholar to the WHO in 1980, Li learned that the organization was studying combined chemotherapy, in a creative approach, to cure leprosy patients. The pharmaceutical formulation had been completed, but there was not enough clinical data. Therefore, she applied for free medicine and support from WHO, and started pilot projects in Southwest China in the 1980s.

To promote the new treatment method that turned lifelong medication into a fixed course for leprosy patients, Li worked painstakingly, and she visited the villagers, door-to-door.

At that time, even though she was in her 60s, she often got up early in the morning and travelled across mountains and rivers to the homes of leprosy patients. She encouraged them to take their medicine.

Li's arrival often brought excitement, and hope of rebirth. Her benevolence and professionalism earned her the nickname "Moyadai," which means "doctor" in the language of the ethnic Dai people.

With concrete efforts, she eliminated people's discrimination against leprosy patients, and proved that the disease is curable.

Rebirth of 'Leprosy Village'

Li has often travelled to far-off areas of Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan provinces to promote leprosy treatment during the past several decades. She has never complained, even though she has suffered several physical injuries as a result of traffic accidents.

Once, on a rainy day in 1987, Li suffered a fracture to the right clavicle, the result of a traffic accident, during a trip from Wenshan to Kunming (both cities in Yunnan Province). To relieve her colleagues' concerns, she just said it was about time she had an accident, since she took a car so frequently to the mountainous regions. Li spent just two weeks in hospital for treatment before she returned to Beijing to continue her work.

In another incident, her boat capsized in Yunnan. She joked to those who rescued her from that it was okay for her to wear wet clothes in such hot weather.

In 1993, a high school girl, from Wenshan, contracted leprosy less than half a year before she was expected to take the national college-entrance examination. Li encouraged the girl to continue with her studies while undergoing a special treatment plan, designed to minimize the negative impacts on both her physical appearance and exam preparations. The girl passed the exam and was eventually admitted to a university. She ended up becoming a teacher.

Thanks to Li's efforts, Nanxing Village, in Mengla County, became leprosy-free in 1990. The former "leprosy village" was later renamed Mannanxing, which means "rebirth" in Dai language.

The last time Li visited the village was in 2015, when she was 94. Many of the residents cried when Li told one of the villagers all of the leprosy patients had recovered, and that she might not be able to visit the village again because of her age.

Nowadays, Mannanxing Village has become a prosperous place. Residents can make a decent living by planting rubber trees.

Devotion Never Fades

Thanks to her ceaseless efforts, Li shortened the course of medication for leprosy patients to two years, and she helped reduce the number of leprosy patients, from around 110,000 to fewer than 10,000, in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan provinces. The annualized relapse rate was also reduced to 0.03 percent, much lower than the one-percent standard set by WHO.

Li's treatment method was promoted worldwide by WHO in 1994. In addition, Li in 1996 launched a nationwide campaign, which highlighted vertical treatment, grassroots prevention and early diagnosis, to eradicate the communicable disease.

Her research data and treatment plans have played important roles in helping both China and the world in eliminating leprosy.

In 2001, Li was the recipient of the first-class award of the State Science and Technology Progress Award, one of the highest and most esteemed science and technology awards established by the State Council (the Chinese Government's cabinet), for her scientific research in leprosy. In 2016, she received a lifelong achievement award, for leprosy prevention and control in China, during the 19th International Leprosy Conference, in Beijing.

Li in 2016 submitted her application to join the Communist Party of China (CPC). She wrote in her application that she never regretted her decision to return to China, and that she will continue her fight against leprosy, as a Party member, for the rest of her life.

Speaking during her oath-taking ceremony in 2016, Li said her achievements are closely related to the care and support of the Party, and that she would regret it if there was not a Party flag on her body after her death.

"There is still more for me to do in my effort to defeat leprosy. I am willing to continue to serve the Party, and the people, and to work hard to build a world without the contagious disease," Li says.

Photos Supplied by Han Weikun and Beijing Friendship Hospital

(Women of China English Monthly March 2022 issue)

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号