Decoding Peking Opera Headwear

The word "kuitou" in Peking Opera is the technical term for various kinds of hats and headpieces worn by various characters in traditional Chinese operas. The headpiece worn by an individual represents his/her identity. In Peking Opera, performers wear different headdresses depending on the occasions and characters. The craftspeople's tremendous efforts (of creating the headwear) are worthwhile, as numerous people have rediscovered, through the artworks, the beauty of the classic headgear.

Headwear Culture of Ancient China

In the traditional Han Chinese culture, people believed that since one's whole body was a gift from one's parents, it was important to avoid anything that might injure it, a principle that exemplified filial piety. Based on this ideology, males were required to let their hair grow long, and wearing hats became a rule of social etiquette in ancient times.

Since ancient Chinese society was divided into various social classes, people in each class wore different styles of attire, but only the nobility were permitted to wear formal hats for adornment. People of lower classes could only wrap their heads with cloth. A male was not allowed to wear a formal hat until he attended the official capping ceremony to mark the start of his adulthood, when he turned 20. As a result, various types of formal hats in ancient times, in addition to having value as a piece of personal adornment and social etiquette, also revealed the social classes of people and strict social divisions between the nobility and common people.

The formal hat culture of the Han Chinese continued up until the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Later after the Manchurians entered the Central Plains, common people began to wear hats. When Western culture was introduced into China during the late Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), the custom of wearing hats became popular among people from various classes. Different materials and styles of hats marked the social classes of the people who wore them.

Peking Opera Headpieces

The important role, which hats demonstrate on the performance stage, is a mirror reflection of people's daily lives. Through the various Peking Opera headpieces, or "kuitou," worn by the characters on the stage, one may get a glimpse of the historical setting and cultural customs of the era in which they live.

Peking Opera's headpieces fall into the following four categories according to the performers' roles: Guan, kui, mao and Jin.

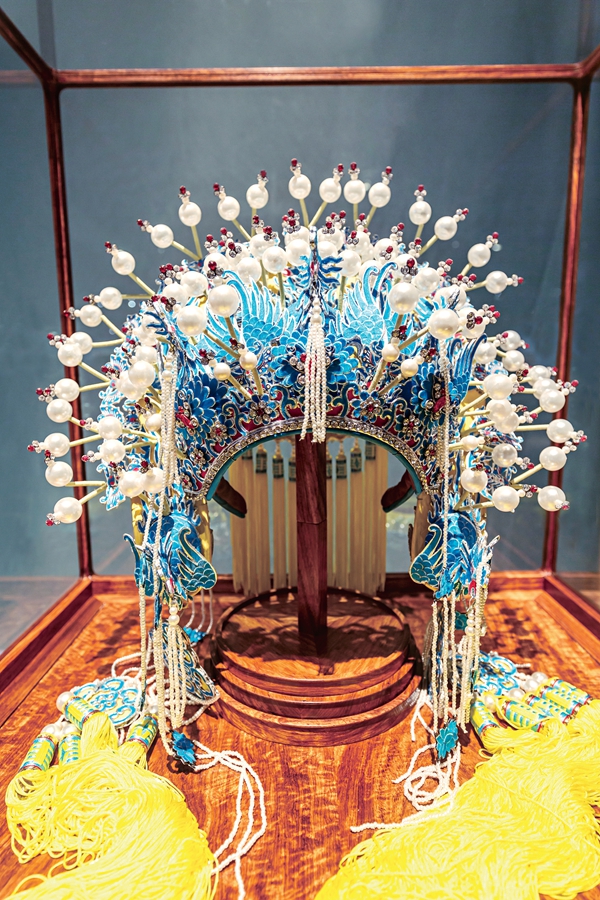

Guan or crown is a formal headpiece that is worn during formal occasions, and persons without a certain position or rank are not allowed to wear it. For example, the formal headpiece worn by the emperor when he goes to court is called the "emperor's coronet," and the young princes and young generals wear purple and golden headpieces. A queen, imperial consort, and other female nobility wear a "phoenix coronet." In total, there are about seven or eight types of coronets or crowns worn by people of different statuses in Peking Opera.

Kui refers to the headpieces worn by military officers to distinguish them from the civilians. In operas generals wear what they call the "commander-in-chiefs' headpieces," which are decorated with bobbles and beads. If a commander-in-chief doesn't wear the formal headpiece, he will cover his head with black cloth, leaving his hair uncovered. This represents that he is defeated in a battle, or is captured by the enemy.

Jin is a hat worn by common people in everyday life with casual clothes, and it is usually made from soft materials. Jin's designs express a more casual state of living, so the items are worn by free, unrestrained scholars or young men of higher classes in Peking Opera plays.

As for mao or hats, they have many designs, many of which are quite complicated. For example, government officials wear black gauze hats, poor people wear felt hats, and foot soldiers wear uniform hats.

The props used in Peking Opera are rather simple, by which the performers may exhibit their talent in acting, singing and fighting. By observing the attire and headpieces worn by the performers, viewers may understand the characters of different people.

Passing on the Craft

In 1967, Yang Donghai was born into a family that made Peking Opera headpieces. His grandfather, Zhang Liancheng, was a master in the headwear industry during the Republic of China (1912-1949). Zhang made headpieces for many famous Peking Opera artists, including Mei Lanfang, Jin Shaoshan, and Ma Lianliang. Yang's parents later followed in his grandfather's footsteps and mastered the skills of making Peking Opera headpieces.

"A complicated Peking Opera headpiece usually takes about several weeks to complete," says Yang. "Take for example the beads on the phoenix crown," he said. "Each bead needs a small spring underneath it to hold it up, so that the bead will slightly shake while the actor/actress is performing. There are about 100 beads on the phoenix crown, and the springs under each of them are all twisted by hand." The colorful phoenix crowns, made by Yang, radiate with the glow of fine craftsmanship.

In addition to inheriting the ancient craft of making Peking Opera headpieces, Yang has spared no effort in promoting the intangible cultural heritage. Each week he travels to various schools to teach children how to make Peking Opera headpieces. To help more children learn about Peking Opera and increase their interest in making Peking Opera headpieces, Yang has tried ways to simplify the process and reduce the difficulties of creating the items.

"Under the influence of our family, my son decided to start learning the family art about five years ago. He has made innovative contributions to promoting the art form. In 2018, he opened his own WeChat public account for spreading the knowledge of folk art," says Yang Donghai. Today, the grandfather, father, and son all teach Peking Opera art classes in schools. Yang Donghai hopes more young people will develop a fondness for the art. He also hopes he will publish a textbook, which will help more people better understand the craft of creating Peking Opera headwear.

Photos Supplied by VCG

(Source: China Today/Women of China English Monthly November 2022 issue)

Please understand that womenofchina.cn,a non-profit, information-communication website, cannot reach every writer before using articles and images. For copyright issues, please contact us by emailing: website@womenofchina.cn. The articles published and opinions expressed on this website represent the opinions of writers and are not necessarily shared by womenofchina.cn.

.jpg)

WeChat

WeChat Weibo

Weibo 京公网安备 11010102004314号

京公网安备 11010102004314号